Between paranoia and slapstick, idealism and anarchy, Groucho Marx and the Una bomber – in his new novel, Thomas Pynchon proves himself to be the grandiose last representative of postmodernism

The trail of the unknown leads quite classically to Ithaca, to that idyllic home port to which this Odysseus never returned after his departure. There, high up in upstate New York, at Cornell University, Thomas Pynchon studied literature and physics in his fifties, interrupted by two years of military service in the Navy, and began to write at the same time.

One of his teachers was the Russian emigrant and refugee from the Revolution Vladimir Nabokov, for whom the worldwide success of “Lolita” would soon enable him to give up his academic work and retire to a Swiss hotel. Nabokov (or rather his wife Vera, who corrected the seminar papers) is said not to have noticed anything more about the student than his illegible handwriting, but it would be nice if after all these years a writing could be found in an archive cabinet, possibly in secret ink, bilingual of course , with which Vladimir Nabokov passes the torch on to his master student Thomas Ruggles Pynchon, giving his final homework to save American literature.

He has taken on the difficult task, he continues to have this duty and yet he has always remained the diligent Cornell student. When Pynchon published a volume of his early stories in 1984, he called him and himself “Slow Learners” (late bloomers), and to this day he studies like a madman, only to then tell his readers what has occupied him for the last few years: thermodynamics , the space-time continuum, quantum physics or the zeros of the Riemann zeta function, as formulated by the mathematician David Hilbert as a problem.

Master of the world’s most challenging books

With the new book, which bears the James Bond-compatible title “Against the Day” and will be available in German translation by the end of 2008, he overwhelms his admirers as usual. Physically, the reactions to each new Pynchon novel are always the same: the tension grows as soon as a new one is announced, rumors about the subject and staff are circulating, all sorts of half-knowledge is peddled, heated discussions about esoteric questions are heated, until excitement inevitably arises coincides when the book is finally out and one critic assures the other that he has seen bigger midgets and that Pynchon was better before.

Aside from the fact that everything used to be better, not least critical judgment, the world (or that small part of it that can read) owes Thomas Pynchon the most challenging books imaginable. Since they are at the same time the funniest and this humor is sometimes quite questionable, despite all the love, the reader, who is covered in the usual goods, often does not know where he is with this author.

«Against the Day» begins in 1893 with an airship ride to the Chicago World’s Fair. Six “Chums of Chance” travel in the vehicle with the strange name “Inconvenience” (which probably means inconvenience) and bear such curious names as Randolph St. Cosmo and Chick Counterfly, not to mention the dog Pugnax, who is duly barks, but also communicates what he is reading. Only the best, of course, and completely up to date: Henry James.

The balloons, which in Pynchon’s novel “Mason & Dixon” (1997) were supposed to both mark and observe the border to the wilderness and, unsurprisingly, were an important part of a huge Jesuit conspiracy against the Enlightenment, have become a pre-zeppelin airship, even more Jean Paul and the moon traveler Cyrano de Bergerac committed as the count of the same name or the Wright brothers – a means of transport of technical imagination, at a suitable distance to the world flying away underneath, which only guarantees the right top view. Balloon, the dog, the five (six) friends, world exhibition. Is he all serious?

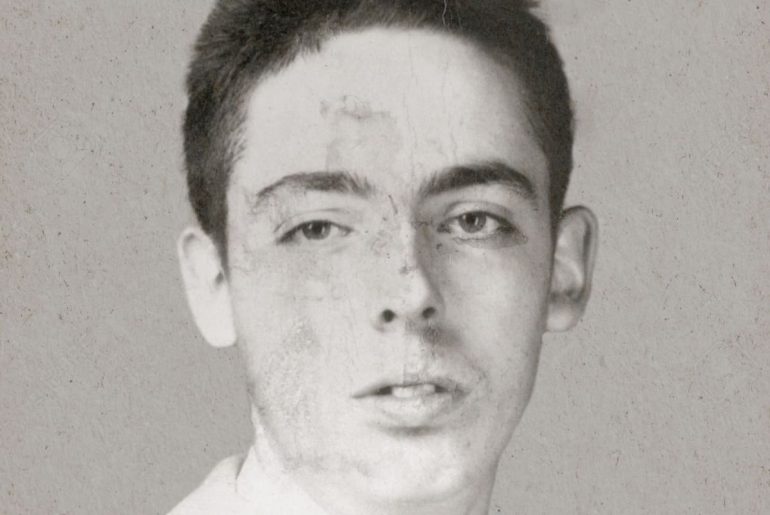

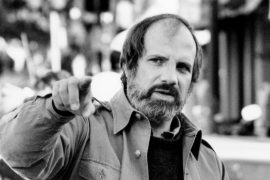

A writer who doesn’t want to be seen

An essential part of Thomas Pynchon’s constant stimulus-response scheme is the legend of the Great Invisible. There are only three reasonably decent youthful portraits in college yearbooks or from his military record. He literally avoided further recordings, sometimes by a hair’s breadth. Long before Michel Foucault buried the author in the sand by the sea, Pynchon withdrew from the world and no longer wanted to be seen or even touched, just to write. He has lived in Manhattan for many years now, is married to his agent Melanie Jackson and continues to shy away from the public eye like, well, the devil shuns holy water. The two have a son, whom he used to take to school. CNN reporters ambushed him, and even then he managed to avert television exposure once again.

Like everyone else, he lives in the present. In a series about the Seven Deadly Sins that The New York Times hosted a few years ago, Pynchon wrote the piece about the inertia, the sloth that ties him to the television. When the book was published, he parodied himself and his self-created image in the appropriate style: he gave his last signs of life on television. He appeared in the series “The Simpsons” as a cartoon character Th. P., his face hidden in a paper bag and said: nothing.

So it was counted again (1085 pages), weighed (one and a half kilos) and, as expected, found to be too light (“superficial characterization”, “confusing” and, proven lightning judgment, “loooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooding”). However, anyone who is not satisfied with devoutly naming the sheer number of pages that “Against the Day” can boast of, who does not already replace the author’s non-existence in the media with acquaintance with him, will have to admit that in the Contemporary literature of the reasonably manageable Indo-European languages is not a more difficult author.

The philologists also know the reason for this: Pynchon speaks in voices like nobody else, and that he only develops his own in the polyphonic verbiage of his personage will only be noticed by those who dare to delve into this gigantic work. He will then also experience that it is quite classically about the fragments of a total novel. Pynchon is the last exponent of postmodernism, which began roughly in 1759 when the first volume of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy appeared. If James Joyce boasted that Dublin could be rebuilt according to the instructions in his books, Pynchon goes for entire continents of yesterday’s world.

Why this author is so difficult

The fact that it’s not the one of today causes some irritation among the performers. Like, no Iraq comment, no 9/11 tragedy, no suburban family falling apart? But a genre piece from such a boring past? It is not without reason that the historical novel fell into disrepair and is otherwise in good hands with Napoleon’s great love and the last sighs of double-suicidal archdukes. But the years before the First World War, the time of the industrial explosion and the first globalization, in which the weapons technology for the coming murders was invented and quickly produced to series maturity, remained strangely untreated.

It was a relentlessly optimistic era, with global plans – or at least the corresponding corporations – and an unexpected economic miracle, the proceeds of which were invested in an unprecedented armament program. The Americans, the Germans and the Belgians took a stand against the established colonial empires of England, France and Holland and demanded a place in the sun for their part, i.e. the largest naval program, the fattest “fat Bertas”, monopolized access to raw materials (ultimately the automobile had just been invented and the airplane would soon be decisive not only for war but also for peace). In all the boasting, says Pynchon, the war began, for which the shots did not first have to be fired in Sarajevo.

The innocent years before the First World War

His early story, Under the Seal, speaks somewhat boastfully of a Masonic lodge waiting until then: “For the fall of Khartoum and for the crisis in Afghanistan to escalate to a point that would allow it to speak of inevitable apocalypse.” In his first novel “V.”, Pynchon has this interface of modern history, which is actually only known to him, where the English and French stalk each other, Germans and Austrians are already involved and the world threatens to get lost unnoticed by the world. (1963) and unfolded in «Against the Day» into a gigantic panorama of the apparently innocent years before the outbreak of the First World War.

It is the time of workers’ struggles and bourgeois garden bars; the natural sciences have emancipated themselves from classical education and are dedicated to pure teaching, and Archduke Franz Ferdinand desires to shoot pigs in Chicago of all places, the city that supplies the world with canned meat. At best, the Viennese fin de siècle finds itself somewhat darkened in this frenetic upheaval, and Kit Traverse, who visits a psychiatrist in Göttingen, experiences a classic German anti-Semite who warns Americans about foreign infiltration by the Jews.

It all started with the Fashoda crisis

Pynchon identifies the Fashoda crisis of 1898 as the starting point for the disastrous 20th century – an analysis that neither Eric Hobsbawm nor Hans-Ulrich Wehler backs up, but which is made for the most imaginative conspiracy theorist in literature today. And just think, he’s even right about that: The arc that he spans in his apocalyptic World War II novel “Gravity’s Rainbow” (The Ends of the Parable, 1973) leads from the forced laborers who worked in Mittelbau-Dora for Albert Speer and Wernher von Braun toiled away, without detours to the American Apollo moon program. The American soldier Tyrone Slothrop embodies the insanity of this war-essential rocket program, with which London was initially supposed to be reduced to rubble and ashes. His erections indicate the next impacts of the V 1 in the city. Or as Pynchon puts it: “Lovely morning, World War Two.”

This author is driven by the student need not only to see through the world, but also to save it. To make it as short as the novel absolutely doesn’t want to be: Thomas Pynchon continued the great novel about explaining the world that he began in 1959 in Cornell. He won’t quite succeed, but with this new fragment of a single large alternative world design, he is approaching an ideal that Jorge Luis Borges once attributed to a cartographer – being able to depict the world on a scale of 1:1. You can still tell that the almost seventy-year-old is a brilliant college student who amazes his friends and professors with his far-reaching, often adventurous, often just extravagant theories.

Therefore, a big warning sign should be put up here: Pynchon is not interested in the adultery and family stories with which the older American contemporary literature in the post-war period made a very profitable living. Psychology, even character drawing, is alien to this great Demiurge. He is a hobbyist, an engineer and wants nothing less than to unravel the mysteries of the world. It used to be a trifle that helped religion, no matter what, and later Christianity diluted to existentialism. In the case of Pynchon, the descendant of a dark Puritan family, however, the world has always been the devil’s; in retrospect, he designs a dystopia for it and, tragically belatedly, braces himself against falling into decline.

There are storylines by the dozen

At Cornell, the intellectual Pynchon admired his peer Richard Fariña, who easily fooled the others into believing that he had spent his term break in Ireland fighting for the IRA and had moved into Havana on New Year’s Eve 1959 with Fidel Castro. This was the doer that Pynchon couldn’t be. That’s why he died with his motorcycle, while Pynchon spent the sixties as a perpetual student and couch potato and wrote his fantastic World War II novel “Gravity’s Rainbow”. IRA and Cuba, that was nice, but he thought big, so he turned down the offer to start as a film critic in New York and instead looked after the company newspaper for the Boeing plants in Seattle. Richard Fariña, at whose wedding to Mimi Baez, sister of folk singer Joan Baez, Pynchon was best man, and to whose novel Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me (1966) he wrote an introduction, returns in « Against the Day» as Dinamitero forty years after his death.

The plot, as far as the almost three dozen strands result in one at all: Webb Traverse, an anarchist explosives expert who, disguised as a miner, blows up bridges and mines, is in turn murdered on behalf of the plutocrat Scarsdale Vibe. His children want to avenge him and are now being pursued by the villain’s henchmen themselves. So far, so good, so adventurous and at the same time familiar, as you know it from a hundred thousand and one pulp novels. Pynchon, as the reader soon suspects, has read them all and is trying very hard to write in exactly the same style.

But he can do even more: he is just as fluent in the style of the youth book as in “Harry Potter”, as in Edgar Wallace, as in John Buchan, as in Dashiell Hammett (whose half-forgotten Pinkerton novel “Red Harvest” is another great role model, but only one of many). Will, the reader asks anxiously, knowing better, will good prevail?

Pynchon, faithful to the dreams of his youthful reading, leaves no trivial cliché unused, which sometimes allows him the most surprising punch lines. Willis Turnstone is able to happily avert a robbery in the Wild West because the robber suffers from back pain at the right moment and Turnstone can give him relief with a professional thumb pressure massage.

A world explanatory novel as a nightmare journey

Anyone who treats his material in such a frivolous manner is not entirely comfortable with the criticism. The book is also not suitable for reading over the weekend or on two or three free evenings. It is too vast, populated by too many people, too educated and too finely woven for that. When the Reverend Moss Gatlin appears, preaching not God but anarchy, there come “unemployed men from out of town, exhausted, unwashed, bloated, sullen… Church members waiting for an opportunity to let it all loose… Women in astonishing numbers, all with the insignia of their profession, abrasions from being towed in the meat factories, blinking from the sewing room long into the night in the timelessly bad light, women with headscarves, crocheted curlers, elaborately flowered hats, without a hat, women who after too many hours of lifting, fetching and walking in streets without work just wanted to put their feet up, on their face the hurt they had suffered again … »

In such widely swinging paratactic sequences, the frantic narrative pace comes to a temporary halt before the scene, the time, the personnel change, new dangers threaten, new conspiracies, new explosions – and not all triggered by dynamite.

In Siberia, far behind the Urals, the taiga blew up in 1908 with 1150 times the explosive power of the Hiroshima bomb: the Tunguska event, which actually took place almost a hundred years ago and was described, for example, by Stanislaw Lem in his novel “The Astronauts”. was treated. Was it aliens? A meteorite? Or is it a man-made explosion, the first test of a weapon of mass destruction? (Maybe Against the Day isn’t a historical novel after all.)

Sympathy for the beautiful souls of terror

The book leads on a never-ending nightmare journey, depicting a more or less conscious flickering of overstimulated brainwaves, where a ride in a submarine under the desert sands has to be the most normal thing in the world. In the course of the thousand-pager, Chicago is followed by the Wild West and Mexico, which were still somewhat of a stretch at the time, as well as Belgium, Germany, Italy, Siberia and, again and again, the Balkans in Europe.

Here, in Sarajevo, the great civil war of the 20th century began in 1914 with the shooting of the well-known archduke. Pynchon’s sympathies for bomb-throwing anarchism are unmistakable. At the time of the declining tsarism, the anarchists were considered freedom fighters, the “beautiful souls of terror”, as Hans Magnus Enzensberger also called them. However, they were thoroughly infiltrated by the police and torn apart in endless factional battles.

Just before the turn of the last century, the anarchist spark leapt from the reactionary continent to England and America, where it seemed the only hope for countless immigrants who worked in the meat plants and warehouses of Chicago to the greater glory of the first tycoons. The factory owners fear that there will soon be nothing left to oppose the united power of the workers. Only a war can help: “A general European war, in which every striking worker would be a traitor, would offer the possibility of finishing off the anarchists once and for all.”

Over the years, all sorts of prominent authors have been suspected of actually being Pynchon. J. D. Salinger (with whom he had little connection) was considered Pynchon, who also lived in reclusive life; the guess was William Gaddis or Don DeLillo (with whom he has more in common); even eco-terrorist Theodore Kaczynski, known as the Una Bomber, who fled civilization, was suspected of being a Pynchon incarnation. Kaczynski attacked the modern world, sending explosives to scientists and planting them on airplanes. He is a late descendant of the Luddites to whom Pynchon once wrote an essay, those Luddites who two hundred years ago were overwhelmed by the pace of progress no less than we are today. Since almost nothing is known about Pynchon, he inevitably attracts such speculation. Finally: his work has not been around since the «auction of No. 49» (1966) of a single large, at least global, conspiracy?

A song of praise for dynamite

In «Against the Day» the anarchists get their historical rights. It is not without irony that a middle-class child from the American East Coast, who can count his ancestors back to the High Middle Ages and whose father was a staunch Republican, reminds his compatriots of the buried tradition of workers’ uprisings and anarchistic and naturally rather un-American activities that were back then not only the Austrian Empress Sisi, but also the American President William McKinley fell victim. It was primarily the immigrants who had to pay the price for the enormous economic leap forward. The 12-hour day was the norm in the factories, and the steady influx of people from Europe kept wages at a gratifyingly low level.

Chicago, where Inconvenience docks, was the stronghold of the anarchists. In 1886, after a lockout at a harvester factory in Chicago’s Haymarket, a bomb exploded, killing a dozen people. The police started shooting at the striking workers. Shortly before that, the German anarchist Johann Most, in his book Revolutionary War Science (1884), which was published in New York but in German, recommended the comparatively cheap dynamite to the workers as the means of choice for the “propaganda of the deed” and at the same time delivered such precise building instructions that the book is still largely secret today. “In dynamite,” American anarchists assured one another, “there is more power to bring justice to the oppressed than there is in laws to appease and slay the spirit of unrest and rebellion!”

It confirms the suspicion that not too many people have read Pynchon’s book so far, because the outrage at an author who, after the end of the communist world and the undeniable victory of the capitalist world, subsequently provides an estimate of the consequential costs of this dubious victory, who does not shy away from capitalists Calling plutocrats and visibly applauding while having Kieselguhr Kid (the aforementioned Webb Traverse) blow up the symbols of the enemy’s power like they’re toy houses should be something to be heard by now.

Traveling through the worst of all worlds

So Thomas Pynchon plays the great game of Rudyard Kipling again, and yes, it’s a no-brainer too: he takes the delightfully simple stories of Alexandre Dumas and Arthur Conan Doyle, delivers deceptively similar pastiches of Horatio Alger, and yet amalgamates it all into a Voltaire ‘s tour de force through the worst of all worlds. This world is poor, but always has been. Pynchon shows where it went wrong. Only a youthful idealist still believes that he can see through the world, and that is why he sees the great conspiracy at work everywhere, which he opposes with his own.

There is so much more that needs to be said about this romantic marvel, from the speaking comic names Dahlia Rideout, Heino Vanderjuice, from Professor Renfrew, who is quarreling with his colleague Werfner and all of them Pig Bodine, Vheissu, Mondaugen, Slothrop and Blikero aus follow the earlier novels. Pynchon has always irritated his friends and enemies with his resolute infantilism, his indomitable joy in slapstick, in immature student humor. Frivolity, carelessness, and of all things when it comes to the most difficult issues, war, mass destruction, workers’ struggles and explosions, that just doesn’t work. But, ut fabula docet, it works.

In addition to the all-dominant paranoia, all the bad habits of the drug-heavy sixties are gathered here – not even sadomasochistic sexual practices anymore, but absolutely disgusting, a dog that can read, talking ball lightning, a hero who mistakes the Marseillaise for Belgian mayonnaise, a Viennese hotel called “Neue Mutzenbacher”, the inmate of a sanatorium and nursing home, who said “I’m a Berliner!” even before the First Great War. crows and thus drags the US President, who is most popular in Germany, as well as the entire frontline city of Berlin into the corn shit – none of this can be true!

Instead of a Karl Marx, who would have to appear in an exemplary historical novel in order to weigh up the pros and cons of a revolution with Heinrich Heine, Pynchon Groucho conjures Marx out of thin air. However, this anarchist film comedian is so carefully incorporated into the fact-based plot that he is barely recognizable to the naked eye. Frank Traverse wakes up in a hotel room at night to hearing screams from next door and asks if everything is okay. “A boy of about fifteen was crouched against the wall with his eyes wide open. ‘Sure – I’m just keeping the bugs at bay.’ He twitched his eyebrows violently and pretended to brandish a whip. <Return! I said: Back!’

The boy’s name is Julius, and that’s the maiden name of the thick-browed vaudevillist and great comedian who may actually have been in Cripple Creek in 1905.

Yes, and, but: does Pynchon mean all this seriously? That, dear reader, you have to find out for yourself.

What is Thomas Pynchon known for?

Thomas Pynchon, (born May 8, 1937, Glen Cove, Long Island, New York, U.S.), American novelist and short-story writer whose works combine black humour and fantasy to depict human alienation in the chaos of modern society.

Who is Thomas Pynchon and why?

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon, Jr.

(born May 8, 1937) is an American writer based in New York City. He is noted for his dense and complex works of fiction. Hailing from Long Island, Pynchon spent two years in the United States Navy and earned an English degree from Cornell University.

How old is Thomas Pynchon?

85 years

Is Thomas Pynchon JD Salinger?

Salinger and Thomas Pynchon are one and the same writer. Salinger is the author of the famed Catcher in the Rye, and Pynchon wrote Gravity’s Rainbow, one of the great novels of the 20th century.

Is Thomas Pynchon a real person?

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr.

(born May 8, 1937) is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, genres and themes, including history, music, science, and mathematics.

Where should I start with Thomas Pynchon?

Inherent Vice (1990) Read this one first.

The Crying of Lot 49 (1966)

Vineland (1990)

Bleeding Edge (2013)

Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

V (1963)

Mason & Dixon (1997)

Against The Day (2006)

Why is Pynchon hard reading?

Don’t believe what you’ve heard, and here’s what you’ve probably heard: Thomas Pynchon’s novels are brilliant but difficult; the multiple plots twist and turn and rarely resolve; there are a gazillion characters; you’ll need a dictionary and an encyclopedia to understand all the scientific metaphors, historical …

Is The Crying of Lot 49 difficult?

“The Crying of Lot 49” by Thomas Pynchon was definitely one of the more difficult novels I’ve ever read. Knowing nothing about the novel, I usually will do exactly what you’re not supposed to do and “judge a book by its cover”. Even in doing that, I couldn’t get much of an idea about what I was about to read.