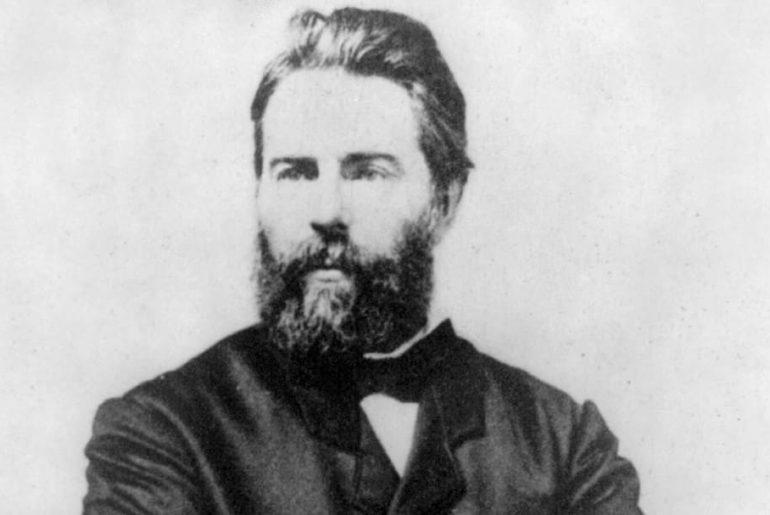

When Herman Melville died of heart failure on September 28, 1891, his literary fame had faded into oblivion. Her widow, Elizabeth Shaw, daughter of an eminent Boston judge, published a discreet obituary in the press, noting that her late husband was a writer. It was a gesture of delicacy with an author mistreated by the public and critics. A sailor, a whaler, a bank clerk, a rural teacher, Melville had spent his last years working as an inspector in the New York customs house. Apparently he performed his duties with carelessness and honesty.

Abandoned by the public and scorned by critics, he took refuge in poetry. His lyrical creations circulated in small editions paid for by his own pocket. Appeared in 1876, Clarel, a colossal epic poem —18,000 lines in 150 songs— longer than the Iliad, only caused perplexity and the suspicion that its author had lost his mind. Melville’s funeral summoned only his widow and two of his sisters. His eldest son had committed suicide by shooting herself in the head and his youngest son had disappeared, having run away from home for unknown reasons. The misfortune affected even his own tombstone, as they altered his name, recording Henry instead of Herman.

Nobody would pay much attention to Moby Dick until 1920, when critics rescued the novel and highlighted its merits, assuring that it was a masterpiece. Currently, Moby Dick is considered to be the most representative novel of American literature, the story that best reflects the spirit of a country with a conscience divided between guilt and pride, the yearning for redemption and the will to power, the vocation of universality and the narrowest provincialism.

Melville perceived God as a terrible sovereign who had thrown man into a world of suffering and scarcity, where the possibility of happiness was almost non-existent.

Allegories can be annoying, particularly when their meaning is clear and unequivocal. It has been pointed out countless times that Moby Dick, the White Whale, represents evil. Not the moral evil, but the metaphysical one that accompanies the human being since the Fall. If the albino sperm whale is the embodiment of absolute malice, Captain Ahab would be the champion of good. However, Ahab is not a hero. Haunted by the humiliation inflicted by the White Whale, who amputated his leg, he does not seek justice, but revenge, even if his price is the loss of his ship and the death of his men. It seems more likely to me to say that Moby Dick is a metaphor for God. In fact, whalers who have survived his attacks claim that he is immortal and ubiquitous. From this perspective, it can be ventured that Ahab is an Adam who does not forgive his creator for expulsion from paradise. Educated in the severe principles of Calvinism, Melville perceived God as a terrible sovereign who had thrown man into a world of suffering and scarcity, where the possibility of happiness was almost non-existent. One could only resignedly accept that fate or rebel against it. Ahab chooses to rebel and God punishes him, burying him under the waters.

In his correspondence with Nathaniel Hawthorne, Melville states that Moby Dick is a “wicked” book. His vision of his universe could not be more subversive: man is corrupt to the root; God perhaps does not exist and if he exists, he does not notice our world, an insignificant point in the cosmos; death reduces everything to insignificance: fame, wealth, wisdom. We know very little, almost nothing. The big questions will never find an answer.

Melville only believed in American democracy. The United States is the chosen people, the nation that carries on its shoulders the ark of freedom. In Casaca Blanca (1850), Melville writes: “The past is dead and has no resurrection; but the future is imbued with so much life that it lives for us even in advance.” The Manifest Destiny of the United States is not to expand from the Atlantic to the Pacific, as the journalist John L. O’Sullivan claimed, but to spread the democratic principles of fraternity and liberty throughout the world. The Declaration of Independence does not spring from nothing, but from a universal lineage forged by great spirits, such as Paul of Tarsus, Luther, Homer and Shakespeare. Melville is not a hot-headed patriot. He admits that the United States has committed serious sins, such as slavery, racism and imperialism. His desire to dominate resembles Ahab’s madness; his violence against his real or imagined opponents evokes the wrath of the White Whale. America is great for its hubris, but that greed could also be the cause of its destruction.

Melville believes that patriotism should be linked to the values of the Enlightenment, not to an expansionist mysticism that justifies illegal wars. This critical vision permeates Moby Dick, transforming it into the great American epic, the chronicle of a colossal undertaking that has given birth to splendor and misery, heroism and vileness, love of life and an irrepressible death instinct. Melville is not Ajab, but Ishmael, the witness of the recklessness and excess of the captain of the Pequod or, if you prefer, of America intoxicated with power that does not accept any limits.

Herman Melville was born on August 1, 1819 into a wealthy family. His father, Allan, was a cultured man who had traveled Europe and his mother, Mary Gansevoort, a refined, educated woman with sincere religious piety. For the first five years of their marriage, they lived in Albany, but then moved to New York to open a French lingerie business. Herman was born there, the third of eleven children.

In 1830, the family business went bankrupt and Allan went mad. He died shortly after, leaving as his only inheritance an accumulation of debts. Herman had no choice but to drop out of school. He worked in a bank, a warehouse, a farm and, at seventeen, he embarked as a cabin boy on a ship bound for Liverpool. Years later, he would write: “The need to do something for myself, coupled with a natural disposition for wandering, conspired within me to cast myself out to sea as a sailor.”

After his first maritime adventure, he worked as a school teacher, but found his experience unrewarding. He soon returned to the sea. In 1841 he sailed from New Bedford on the whaler Acushnet, bound for the Pacific. His relationship with his classmates was not easy. Despite his sympathy for the less favored classes, his manners and knowledge collided with the brutality and ignorance of the crew. That paradox would lead to a painful isolation.

He boarded the first boat to arrive on the island, not without wrestling with his guests, upset at his departure, which perhaps deprived them of a long overdue lunch.

Fifteen months later, the whaler dropped anchor at Nuku Hiva, an island in the Marquesas. Melville went inside with another sailor, fleeing life on board, increasingly unbearable. The Taipi welcomed them hospitably, despite being cannibals. Abandoned by his accomplice, Melville spent four months among the natives, enjoying a comfortable and relaxed existence, but he got on the first ship that arrived at the island, not without a fight with his guests, upset by his departure, which perhaps deprived them of of a long overdue lunch. It is said that he killed an indigenous man with a boat hook, but it is not known for certain. The ship that picked him up was another whaler, the Julia, and his routine was as hellish as that of the Acushnet. In fact, the crew mutinied in Tahiti. Melville ended up on the island of Moorea, planting potatoes for a small wage, but he didn’t last long. He embarked on another whaler, which he called Leviathan and which took him to Honolulu. He would once again sail on an American frigate, the United States, where he served as a common seaman.

Unstable, unpredictable and withdrawn, W. Somerset Maugham attributes repressed homosexual tendencies to him, relying on some particularly fiery descriptions of his male friends, such as Tobias Greene, the boy who eloped with him from the Acushnet: “His naturally dark skin had gone darkening from exposure to the tropical sun, and a mass of jet-colored curls gathered at his temples, and cast a darker shadow over his large black eyes. In Liverpool, Melville befriended a boy named Harry Bolton, whom he would describe in no less fiery tone: “His skin was of a dark tinge, feminine as a girl’s; […] Her voice was like the sound of a harp.” Somerset Maugham points out that Melville did not deviate from the morals of his day, but he allowed his imagination to take certain liberties. That tension could have affected his character, since these were not harmless fantasies, but desires that were considered perverse and subject to severe prison sentences, not to mention scandal and social disapproval. Was Maugham wrong? We cannot answer unequivocally, but there is no doubt that Melville was a tormented and mysterious man, who grew up with an acute feeling of helplessness caused by the death of his father, the ruin and disdain of his mother, who did not approve of his inconstancy and his tendency to slack off.

In the immensity of the sea, Melville felt that man had been abandoned by God. When he returned to the United States at the age of twenty-five, his adventures aroused the interest of family and friends, who encouraged him to write. He would emerge that way Taipi. A cannibal Eden, his first book. Published in 1846—first in London and then in New York—it enjoyed moderate success. Melville narrates his adventures in the South Seas with a sensual prose that oscillates between travelogue, ethnography and social criticism: “The Marquesas! What strange visions of exotic things this very name evokes! Naked houris, cannibalistic feasts, coconut groves, coral reefs, tattooed wrens, and bamboo temples.” Melville incurs the prejudices of Western civilization towards other cultures, but at the same time celebrates a society free of greed and moral repression, a kind of Arcadia that has not yet suffered the ravages of capitalism and Christianity.

Taipi’s success prompted him to write a second play entitled Omoo, which—in the native language—means “wanderer.” Published in 1847, it continues the account of his experiences in the South Seas. His criticism of the exploitation suffered by the indigenous people at the hands of their alleged civilizers aroused the wrath of politicians and missionaries. Faced with the asceticism of the Christian tradition, Melville exalts the freedom of the natives, who live in perfect harmony with nature, oblivious to feelings of guilt and sin. That same year, he married and settled in New York. He is born to his first child, Malcolm, and travels to Europe to meet with potential publishers of his next books.

In 1849, Mardi appears: and a journey beyond. His initial intention was to write an adventure set in the Pacific, but his readings and an increasingly demanding conception of writing as a form of knowledge will transform the work into an allegorical journey through the imaginary Mardi archipelago, threaded with reflections on the myth of the Fall, the meaning of suffering and the problem of evil. Melville raises the possibility of a cosmos without God or, what is more frightening, with an indifferent God. A satirical-philosophical novel inspired by Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus (The Patched Tailor), Mardi sold poorly and baffled readers, who were expecting a new adventure book. Melville, who had been deluded by the prospect of making a living from literature, hastily wrote Redburn: His First Voyage (1849) and White Coat; or the world of the warrior (1850), which once again spoke of his youthful travels through Europe and the Pacific.

‘Mardi’ sold poorly and baffled readers, who were expecting a new adventure book. Melville hastily wrote ‘Redburn’ and ‘White Coat’

Influenced by reading Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, Redburn is riddled with autobiographical elements: family bankruptcy, early poverty, the trip to Liverpool, and the return to America, a nation that still played the role of refuge. and asylum for the disinherited of the earth. White Coat narrates life aboard an American warship, denouncing the brutal discipline of the officers with the crew. Marked by the reading of Emerson, Melville praises the democratic brotherhood and calls for the moral regeneration of society. He is not a revolutionary, but he is very critical of classism and rigid hierarchies.

In the fall of 1850, Melville takes out a loan from his mother-in-law to buy Arrowhead, a farm in Pittsfield. Among his neighbors is Nathaniel Hawthorne, with whom he will maintain a close friendship for fifteen intense months. At that time, he has already started working on Moby Dick, with such dedication that his family fears for his health. The relationship with Hawthorne begins in a very literary way, when both take shelter from a storm under a rock. During the storm, they talk about literature and religious issues. From then on, they will spend long evenings chatting animatedly, often until dawn breaks. Between shots of brandy and good cigars, they exchange impressions. Melville’s infatuation is sometimes embarrassing: “I have the impression that I will leave the world more satisfied to have met you.” Moved by that fervor, he dedicates Moby Dick to his friend “as a sign of admiration for his genius.” Hawthorne sends him a letter commenting on the novel. It is lost, but we retain Melville’s emphatic reply: “His heartbeat in my ribs and mine in his, and theirs in God. That you have understood the book has produced in me a feeling of inexpressible security. I have written a devilish book and I feel pure as a lamb”. A supporter of “an unconditional democracy in all things”, Melville confesses that he feels “aversion for the human race”. Or, more exactly, by “the mass”. He considers democratic egalitarianism to be compatible with the vindication of the “aristocracy of the brain”. In a corrupt society, the hero can only be a rebel, which will mean that many consider him a criminal.

Melville and Hawthorne will only see each other twice. Some point out that the author of The Scarlet Letter felt uncomfortable with the intensity of his friend and tried to distance himself from him. Melville will refer to his long evenings as nights of “ontological heroics.” Hawthorne seems as profound to him as Shakespeare. In his work, he appreciates compassion, love and a certain fatality that he defines as “blackness”. Despite his ambition, Moby Dick, or the Whale, published in 1851, receives a cool reception. In the United States, an edition of 3,000 copies is published. In the United Kingdom, only 300 are published. Neither edition sold out during Melville’s lifetime. Readers’ reticence turned to hostility when accusations of blasphemy began to circulate, a crime that at the time could carry a prison sentence. Son-in-law of a notable judge, the family pressured the writer to attend divine services, but he refused. He had embarked on a path of no return. He was no longer looking for success, but rather the recognition reserved for the greatest writers, almost always misunderstood by his contemporaries. He was not a cursed, but he was a rare and unclassifiable feather. His next novel, Pierre or the ambiguities (1852), definitively stripped him of the support of the public and publishers. Incestuous love story between stepbrothers, a critic appreciated its enormous dramatic force and defined the work as “the tragedy of an American Hamlet”. In its pages, it is clear that Melville has settled into an implacable nihilism. There is definitely no God and if he exists, he doesn’t care about us. It is not possible to know others or oneself. The mind is an ocean of abyssal depth, cloudy and unfathomable. Knowledge is only a mirage. The truth is always elusive. It is only possible to adopt a heroic, lonely and hopeless resistance against an indifferent universe and a decadent society.

3,000 copies of ‘Moby Dick’ were published in the US and only 300 in the UK. Neither edition sold out during Melville’s lifetime

Exhausted and on the verge of mental collapse, Melville still published fourteen stories and sketches anonymously between 1853 and 1856 in Putnam’s and Harper’s magazines. Among them there are masterpieces, such as Bartleby, the clerk and Benito Cereno. His paymasters had demanded that he not address complex or offensive topics. Melville accommodates these demands, practicing the art of irony and allusion. Bartleby is a new Ahab, but he no longer wants revenge on a God who has betrayed his promises. He just lets himself die. It is a silent revenge, but full of rage. Benito Cereno prefigures the plots of Joseph Conrad, with characters thrown into labyrinths with no way out, condemned to fail and disappoint those who had placed great expectations in them. At the end of these anonymous accounts, Melville is thirty-seven years old. He is old, abuses alcohol and has failed as a writer. He dedicates himself to writing poems that reflect his disappointment with everything. He has doubts about the role of the United States as the herald of a brotherly democracy and does not believe in a transcendent God. The only thing sacred is life, infinite and imperfect and of dramatic beauty. Melville moved to New York, where he died at the age of seventy-two. Hardly anyone remembered him and his books were hardly read. He left behind a posthumous and unfinished work, Billy Budd, which would not appear until 1924. Billy Budd is a sailor wrongfully sentenced to death. The only crime of his is his youth and his innocence. Before being executed, Billy forgives the executioners of him. Perhaps Melville wanted to tell us that he said goodbye to the world without rancor.

Moby Dick is a classic because it deals with the great themes that have never ceased to concern human beings: friendship, education, the transition to maturity, the struggle between good and evil, the existence —or absence— of God, politics and social order, the conflict between civilization and nature. Moby Dick is the story of a frustrated deicide. The deed of the Pequod announces the definitive loss of confidence in divine providence. Ahab is a new Adam, but he does not represent a beginning, but rather the twilight of hope, the end of certainties, the hegemony of dust over life, of nothingness over being. Moby Dick is not evil, but that God who has abandoned man to his fate, remembering him only when he dares to challenge him. Imbued in the reading of the Bible, Aeschylus, Shakespeare, Milton, Goethe and Carlyle, Herman Melville resorts to the myth of dragons and sea monsters that embody the forces of chaos, quoting in the preliminary “Excerpts” from the prophet Isaiah: “That day The Lord will punish with his sword, fierce and powerful, Leviathan, the elusive serpent, Leviathan, the crooked serpent, and he will kill the dragon that lives in the sea” (27, 1). Melville reverses Bible prophecy. Ahab is that fierce and powerful sword, but the Leviathan is not the devil, but God himself. Perhaps the chaos is not the result of the Fall, but of the laziness of the creator, whose acts are as incomprehensible as the most hermetic hieroglyphics.

Melville fused the myths of the Old World (Perseus, Saint George) with the spirit of the New, without a tradition of epic literature, but with an unlimited confidence in his destiny as a beacon and foam of the future. The Quaker captain of the Pequod exudes the same grandeur and fatalism as the heroes of Shakespeare’s tragedies. Ismael is not a particularly seductive figure, perhaps because his personality is forged during the hunt for the White Whale. Witness and sole survivor of the tragedy, he will establish a close bond of friendship with the harpooner Queequeg, the noble savage. The young sailor and the cannibal will establish such an intimate relationship that they will become “inseparable twins”. It can be said that they embody the double face of Melville: on the one hand, the concern to learn, the desire to create, the desire for adventure, and, on the other, the immediacy of natural life, the innocence of primitive man, the freedom of living without philosophical or theological dogmas. Melville dreamed of a community of spirits with a high and creative mind. He felt he was getting closer to that goal during his friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne, but in the years spent with the Marquesas Indians he also saw greatness. Melville’s aim to overcome the oppressive and alienating Western perspective perhaps explains the Pequod’s crew of blacks, easterners, mestizos, and outlaws. Ismael affirms that he has not been a pirate. Can we ensure that he is not lying?

Captain Bildad and Captain Peleg are Quakers. They do not embark, but recruit the crew. It is impossible to sympathize with them: authoritarian, solemn, hypocritical, inflexible, greedy. It is the same with the officers: Starbuck, sensible and determined, but afraid of the extraordinary; Stubb, with a courage born of his defective imagination, unable to notice danger; Flask, ignorant, unaware and without a shred of sensitivity. By contrast, you don’t have to look too hard to appreciate the three harpooners: Queequeg, a cannibal with a ghostly tattooed face, but “a simple and honest heart”; Tashtego, a redskin with the untainted blood of his proud ancestors; Daggoo, a corpulent and majestic black man who involuntarily arouses in his companions a feeling of “physical humility”. Melville professes the religion of the “great democratic God”, where racial differences are doomed to melt into a flame of brotherhood.

The harpooners do not hate the whales they hunt, perhaps because they have never thought that they live under the protection of a father God. On the contrary, Ahab allows himself to be carried away by a “bold, inexhaustible and supernatural revenge” because he has discovered the helplessness of man before the cosmos. His monomania is born from a childish spite that Ismael will come to share. Both are orphans, insignificant creatures in the dance of being, where life and death follow each other without purpose or purpose. God has forsaken man, but continues to mistreat him with his wrath. Father Mapple’s homily, heard by Ismael in the Whalers’ Chapel before embarking, travels the seas, showing that the sacred is not something benevolent, but rather terrible and implacable. Father Mapple preaches from a bow-shaped pulpit, proclaiming that eternity belongs only to God. The kingdom of man is death. The priest’s words are ambiguous and imprecise. If they are interpreted with any audacity, it could be thought that God is sick, almost dying, and he will not tolerate man surviving him.

Melville set out to map the cosmos. Given the vastness of it, he chose the sea, a microcosm with the appearance of totality.

Melville has been criticized for his digressions, which would supposedly prove his narrative ineptitude and his pedantry as a school teacher, eager to display his knowledge. Is there another explanation to justify his long explanations about the hunting and butchering of cetaceans, accompanied by detailed taxonomies? Would it be convenient for him to purge these chapters from the reading? Undoubtedly not, because they would disfigure the work. Melville set out to map the cosmos. Given the vastness of it, he chose the sea, a microcosm with the appearance of a whole. In a chaotic and meaningless universe, knowledge is the only sword that can defeat evil, or at least mitigate its devastations.

Melville is not satisfied with narrating the contest between good and evil. He wants to convey to us the soul of the titanic struggle, which requires being exhaustive and meticulous. If Moby Dick had no digressions, it would be an infinitely less valuable novel. The core of it is not intrigue, but the vocation to encompass the universe. It is the same ambition that inspired the Iliad or Dante’s Comedy. Between dust and life, the word emerges, struggling to undermine the empire of death. However, the sword does not defeat the monster. The White Whale destroys the Pequod. Does that mean that Melville ends his song with a terrible failure? No, because there is a survivor, Ishmael, who returns from the last circle of hell. Instead, Melville sends Ahab to the bottom of the ocean. It is a way of exorcising the inner demons from him, of annihilating resentment and dissatisfaction. Ishmael does not claim to be a new Adam, like Ahab, but rather a free man reconciled with finitude. The feeling of emptiness that death causes us can only be combated with the creative energy of life. Ahab is not Prometheus, but a vulgar Othello.

D. H. Lawrence states that Moby Dick “is a symbol. About what? I doubt very much that even Melville didn’t know exactly. That’s the best of all.” It is an open and fruitful hypothesis, since it does not exclude any reading, but I dare to venture that Moby Dick is a branch of the tree of knowledge. Tasting its fruit does not make us gods, but it reminds us that we live in the open. Helpless, but free. Melville was an unhappy man. He did not know glory. He perhaps he lost faith in his work. He did not stop writing, but he did so with the anguish of the creator who is spared recognition. He probably did not suspect that Moby Dick would open the gates of Olympus reserved for geniuses such as Aeschylus, Shakespeare, Milton or Goethe, whom he admired so much. When I think of Melville, I imagine him on the highest mast of the Pequod, acting as a lookout, a hundred feet above our heads, carving out a route that would be navigated by names like James Joyce, William Faulkner, Hermann Broch, and Kafka, heirs to —sometimes unknowingly— from his visionary pen.

What is Herman Melville best known for?

Not until the early 20th century was Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick first recognized as a literary masterpiece and touted as a cornerstone of modern American literature. Born to a New York City merchant in 1819, Melville fought for a greatness that would not be realized during his lifetime.

How did Herman Melville influence literature?

Melville was rediscovered in the 1920s and is now recognized as a starkly original American voice. His major novel Moby-Dick, short stories, and late novella, Billy Budd, Sailor, published posthumously, made daring use of the absurd and grotesque and prefigured later modernist literature.

How did Herman Melville impact the world?

Herman Melville’s writings influenced America mainly after his death as we discovered the underlying beauty and validity of his literature, developed from his years of experience as a seaman. There are many reasons why Herman Melville is considered one of the most decorated literary authors of his time.